Semantic closure: why compilers know when they are right and LLMs do not

The difference between compilers and LLMs is not determinism

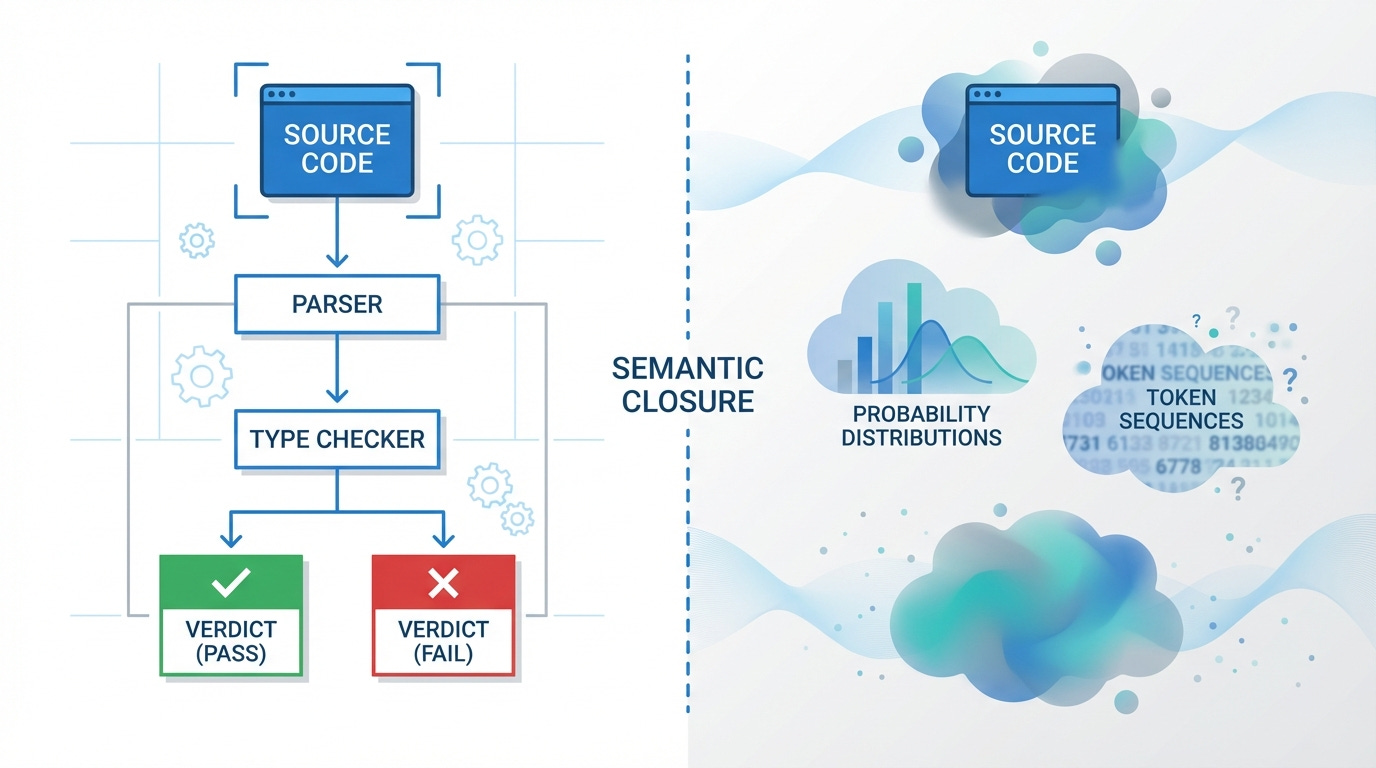

Feed a C compiler a file with a type error. It stops, points to the line, names the mismatch, and refuses to continue. It knows the program is wrong. Not "thinks". Knows. It’s structural: the compiler defined the language, parsed the input according to that definition, checked every constraint, and reached a verdict.

Now ask an LLM to write a function that reverses a linked list. It produces something. The code compiles. Maybe it works. Maybe it silently corrupts memory on lists longer than 255 elements. The model cannot tell you which. It has no mechanism to distinguish between these outcomes.

Compilers are deterministic; LLMs are stochastic. The dividing line is a property called semantic closure.

Semantic closure, defined

A system has semantic closure when it can define, interpret, and verify the meaning and correctness of its own outputs from inside the system.

Meaning is internal. The system contains a complete definition of what valid output looks like.

Validity is self-checkable. The system can examine any output and determine whether it satisfies the definition.

Errors are explicit and decidable. When output fails, the system produces a specific, machine-readable explanation.

No external interpretation is required. Correctness does not depend on a human reading the output and judging it.

The type checker (a metalanguage) verifies the program (an object language). The system as a whole achieves closure.

Semantic closure is a systems property. It describes whether the entire pipeline from input to output contains enough formal structure to judge its own results. It’s always relative to a specification. A compiler verifies that a program conforms to the language's type system and semantic rules. It does not verify that the program matches the programmer's (functional) intent.

TLDR: A function that type-checks but returns the wrong result is "correct" by the compiler's specification and wrong by the programmer's. They work on 2 different layers.

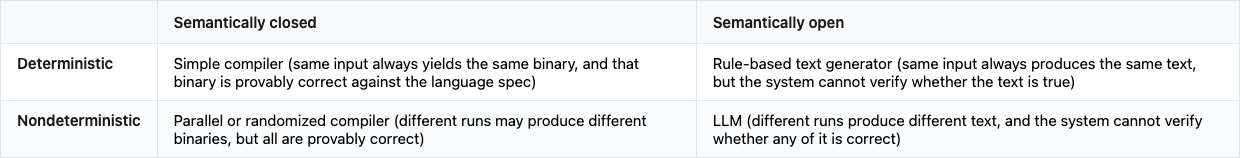

Determinism: a different axis entirely

Determinism means same input, same output.

Determinism concerns repeatability. Semantic closure concerns correctness. These are independent properties.

A system can be repeatable without being correct.

A system can be correct without being repeatable.

The two axes are orthogonal. Conflating them leads to a specific mistake: believing that making an LLM deterministic would make it correct.

Why compilers have semantic closure

Consider this Rust code:

fn add(a: i32, b: &str) -> i32 {

a + b

}The compiler processes it through a stack of formal machinery:

Language definition. Rust's grammar and type system specify exactly what a valid program is. This is a mathematical object: a set of rules that enumerate every legal construction and exclude everything else.

Parsing and type inference. The compiler parses `add` into a typed abstract syntax tree. It infers that `a` is `i32` and `b` is `&str`.

Type checking. The `+` operator on `i32` expects another numeric type on the right. `&str` is not numeric. The compiler has a formal proof that this program violates the type system.

Explicit verdict. The compiler emits:

error[E0277]: cannot add `&str` to `i32`

--> src/main.rs:2:7

|

2 | a + b

| ^ no implementation for `i32 + &str`A definitive, machine-readable statement: this program is ill-typed and will not be compiled.

The Curry-Howard correspondence makes the theoretical foundation explicit: types are propositions, programs are proofs, and the type checker is a proof verifier. A well-typed program is a constructive proof that its type is inhabited. The compiler does not merely check syntax. It verifies a mathematical claim about the type-level behavior of the program.

Every compiler that type-checks source code is exercising semantic closure at some level. The property exists on a spectrum. Rust’s borrow checker provides more closure than C’s type system. The question is always: does the system contain formal machinery that can judge its own output against a defined specification? Compilers do. The machinery is the language definition and the checker.

seL4, a formally verified microkernel, extends the closure chain beyond the compiler. Its 8,700 lines of C are proved (not tested) to be free of buffer overflows, null pointer dereferences, memory leaks, and nontermination. Compile it with a verified toolchain and the semantic guarantees carry through from source to binary.

Nondeterminism doesn’t break semantic closure

GCC is not deterministic. Compile the same file with `-O2` and you get one binary. Compile with `-O3` and you get a different one. Enable link-time optimization (`-flto`) and GCC generates random symbol names. Build on two machines with different directory layouts and the debug info paths differ. Achieving byte-identical builds requires deliberate opt-in: SOURCE_DATE_EPOCH, -frandom-seed, -ffile-prefix-map.

None of this impacts correctness. Correctness means: the compiled binary behaves according to the semantics of the source program. Multiple distinct binaries can satisfy this constraint simultaneously.

Think of it as constraint satisfaction. The source program defines a set of acceptable behaviors. Any binary whose execution falls within that set is correct. The compiler's job is to pick one. Which one it picks may vary across runs, optimization levels, or target architectures. The compiler remains semantically closed because it can verify, for each choice it makes, that the result still falls within the acceptable set.

Can’t we achieve this with LLMs?

Why LLMs lack semantic closure

Ask an LLM to write a function. It produces tokens. Each token is selected as the statistically most likely continuation of the sequence so far. The output is text, shaped by patterns learned from training data.

There is no mechanism for semantic closure in an LLM (we’ll explore below how to add it):

No formal input specification. The input to the LLM is natural language. Natural language is inherently underspecified: it leaves gaps in data models, edge cases, error handling, and security posture. The LLM fills those gaps with statistical inference. A compiler has a formal grammar. An LLM has a probability distribution.

No internal correctness predicate. The compiler can evaluate "does this binary match the source semantics?" because both the source semantics and the evaluation procedure are defined inside the system. The LLM has no equivalent. It cannot evaluate "is this code correct?. This is where compilation stage (run by LLM) is necessary to get a form of validation.

Self-evaluation is more text, not a judgment. When an LLM checks its own output, it generates another sequence of tokens produced by the same statistical process. Research confirms this: LLMs asked to self-correct without external feedback are more likely to change a correct answer to an incorrect one than to fix a mistake.

This is worth pausing on. Huang et al. at ICLR 2024 put the paradox: if the model could judge correctness, why didn't it produce the correct answer in the first place? The model lacks a verification channel separate from its generation channel. Every "check" runs through the same statistical machinery that produced the original output.

Semantic closure requires a formal specification and an internal checker. LLMs have neither.

Why determinism does not fix this

Set temperature to zero. Pin the random seed. Use constrained decoding to force JSON output. You now have a repeatable system. But not a correct one.

Researchers measured accuracy variations of up to 15% across naturally occurring runs at temperature zero. Why? Because temperature zero does not mean deterministic in practice. Batch processing is the culprit: your request shares a GPU with others, and a token winning by a margin of 0.0000001 can flip based on which concurrent request finishes first. Floating-point non-associativity, MoE expert routing, and nondeterministic CUDA kernels add further variation.

But even perfect determinism would not create semantic closure. A deterministic LLM gives you the same answer every time. If that answer is wrong, you get the same wrong answer every time. Determinism addresses repeatability. It says nothing about correctness.

Structured output constraints (forcing JSON schema compliance, regex-matching tokens at generation time) solve the format problem but not the content problem. The output conforms to a shape. Whether the values in that shape are correct remains unverifiable from inside the system.

Format closure is not semantic closure. Knowing that the output is valid JSON tells you nothing about whether the JSON is true.

The fluency trap

MIT researchers found in November 2025 that LLMs learn to associate syntactic templates with domains and answer based on grammar patterns rather than understanding. Their models responded correctly to complete nonsense phrased in familiar syntax and failed on semantically valid questions phrased in unfamiliar syntax.

This is the fluency trap: fluent output triggers processing fluency, a cognitive shortcut where humans perceive well-structured explanations as more trustworthy regardless of factual accuracy. Studies confirm that users preferred LLM responses over template-based alternatives even when the LLM introduced factual inconsistencies.

This is really bad. In the Schwartz v. Avianca case, a lawyer submitted six fabricated case citations generated by ChatGPT. When he asked ChatGPT whether the cases were real, it confirmed they were. The citations had correct formatting, plausible case names, realistic holdings. The AI Hallucination Cases database now tracks 486 cases where lawyers or judges filed documents containing hallucinated content.

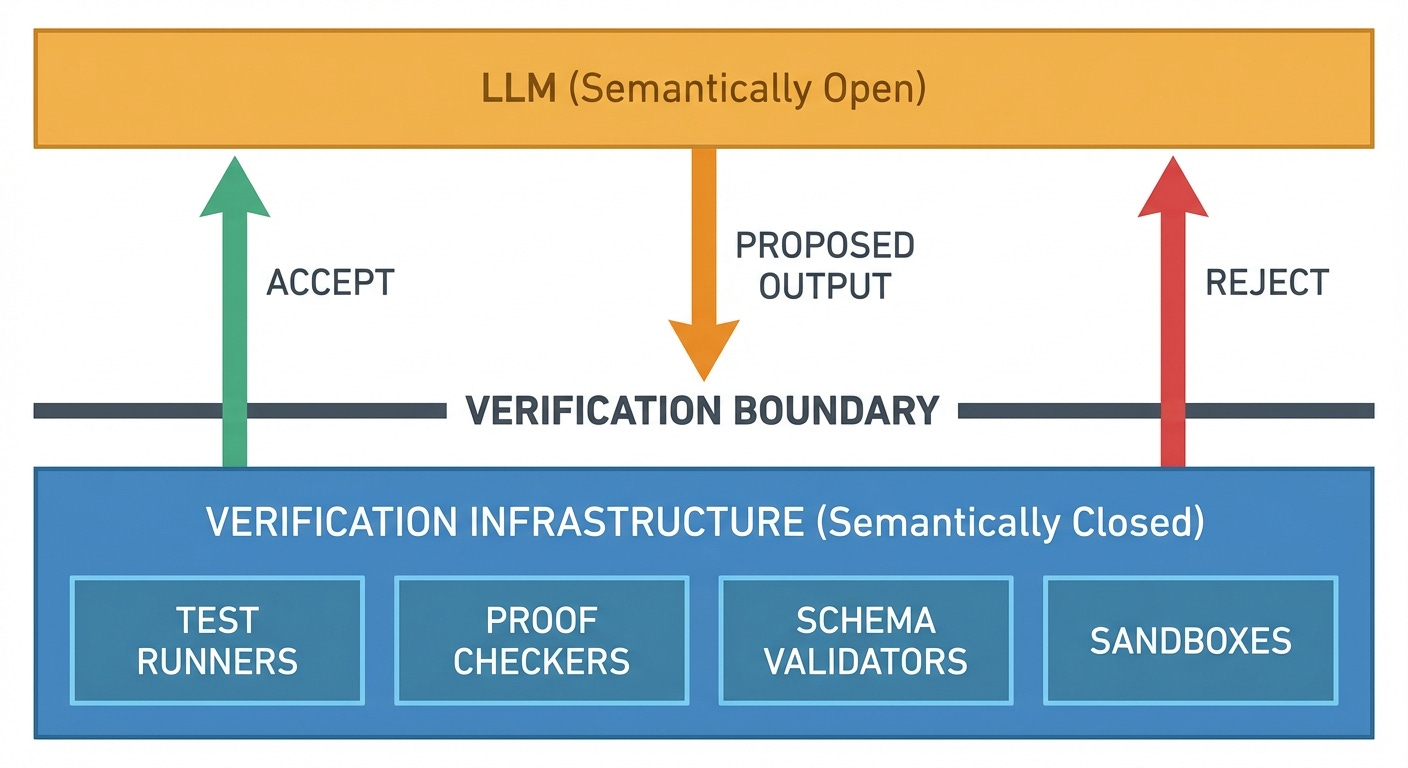

How teams rebuild closure outside the model

Let’s fix it now!

The systems that work in production share one architectural pattern: the LLM proposes, and something else verifies.

Tests. The simplest form of external closure. Write a test suite that defines expected behavior. Run the LLM's code against it. The test runner decides correctness. (read them)

Linters. Static code analysis: code practices, modules dependencies analysis, security issues and unsafe patterns.

Formal verifiers. Martin Kleppmann argues that AI will make formal verification mainstream. His reasoning maps directly to semantic closure: "It doesn't matter if they hallucinate nonsense, because the proof checker will reject any invalid proof." The proof checker is a small, verified system with semantic closure. The LLM generates proof candidates. The checker verifies them. Closure lives in the checker, not the generator. This is already working: the Astrogator system uses formal verification of LLM-generated code and verified correct code in 83% of cases while identifying incorrect code in 92%. Systems like LeanDojo and AlphaProof use LLMs to generate proof candidates for Lean and other proof assistants, with the assistant providing the semantic closure.

Sandboxed execution. Run LLM-generated actions in containers, verify results, support undo. The sandbox provides closure: it can observe whether the action produced the expected state change.

Typed tool boundaries. Production agentic systems increasingly use a three-layer architecture: planners generate intent (LLM), tool routers enforce typed schemas (deterministic), and execution sandboxes run precondition checks and commit or rollback transactionally. The trust boundary sits at the router, not the planner.

All of these approaches share a structure: a semantically open system (the LLM) embedded inside a semantically closed system (the verification infrastructure). The LLM generates candidates. The infrastructure judges them. Closure is a property of the composite system, not of any single component.

Then what?

The question is whether the system around the LLM can verify what it produces. Where verification exists, LLMs strive. Where it does not, it’s stupid as unverifiable.

Build the verification. Then add the LLM.